Art: Ikegami Ryoichi

Story: Fumimura Sho

A political epic about two ambitious young men determined to change the fate of the Japanese nation.This atypical crime-meets-politics thriller was serialized in Big Comic Superior from 1990 to 1995, then released into 12 volumes by Shogakukan. It was collected into nine volumes and published in America by Viz Graphics from 1995 to 1997. Sanctuary was a best-selling title in Japan, and it inspired a live action film. It is also one of the books that has paved the marketplace for adult manga (seinen) in the United States. It was published in France by Kabuto.

Hojo Akira and Asami Chiaki are two men with a master plan. They intend to change the world they live in and the way things have been going. No less. They have chosen two different but parallel paths. One walks in the shadows as a yakuza oyabun (a mafia don), the other in the bright lights of politics. As they rise to the top of Japanese society, where they aspire to find and found a “sanctuary” of their own, they have to face ruthless enemies and formidable factions. Alliances are formed, wars are declared, in both the underworld and the Parliament (called the Diet). Why they want to literally reform the country remains as obscure as their common past in Southeast Asia in the early stages of the story. Progressively revealed, the mystery shrouding their origins adds extra layers of meaning and psychological depth to the characters, whose dimensions take on tragic proportions and are underscored by the realism of Ikegami’s art.

The grand scale of Hojo and Asami’s ambition is clearly shown by the developments of the plot. The pair creates an expanding geography of power: from inside Japan (from the Kanto region to remote areas like Okinawa) to foreign lands like Hong Kong, Russia, and the US, forming, in the process, networks of (virile) loyalty that conquers and converts diverse opponents: brutal mob enforcer Tokai, or mastermind Ibuki, to name a few.

Constructed mostly around Hojo and Asami, the story is distributed into a few subplots involving other yakuzas and politicians, all equally tough (strangely, cops stay in the background and never assume critical importance in the narrative). Those minor, or rather supporting characters, usually appear as powerful antagonists belonging to the old order, but have either hit a dead end or found themselves at a turning point in their lives. After being defeated, countered, or simply convinced, they join forces with Hojo and Asamis side, who represent a new order founded on youth and strength rather than tradition and hierarchy.

Far from a manichean good-vs-evil conflict, the war waged by the two young men brings into questions the legitimacy of the power that be, not power itself. One of the reasons why they are after supremacy, is that they see it is as a sacred space, a sanctuary precisely, not as a factor of tyranny per se. That established politicians and yakuza dons are corrupted by this power is not relevant here. Hojo and Asami challenge them because they abuse their authority to subject “the people” into apathy, and turn them into puppets, drifting from (what they think of as) their original purpose: governing for the sake of the sovereign good, which has no moral implications here.

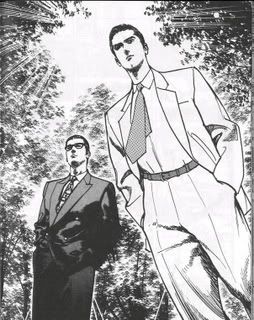

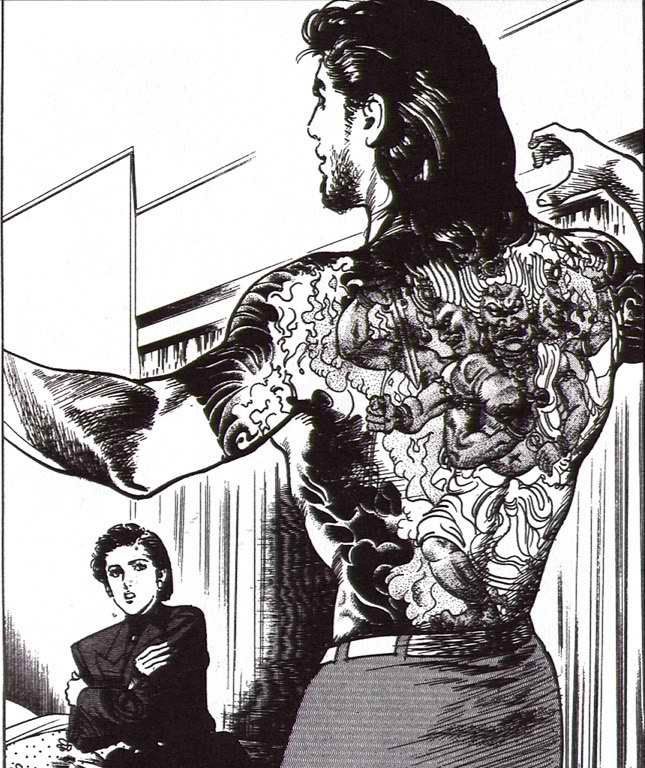

In Sanctuary, Ikegami and Fumimura (also and better known as Buronson) draw a fascinating portrait of a very ambiguous Japan, sometimes dangerously close to reality, where the stakes are breathtakingly high, the design grand, and the characters impossibly charismatic and heroic. Ikegami's art lyrically emphasizes their grandeur with cinematic techniques like low-angle shot look-alike graphics (cf. illustrations above) and creates an intense sense of “cool”. This mise-en-scène is a subtle exploration of the extreme rigidity of a complex hierarchical system based on conservatism, and the relationships of the country with the outside world.

The only flaw of the manga is the many ways in which it projects an unrepentant machismo. While it cleverly shows the intricacies and seductions of power, it is also an uncritical glorification of masculinity, enshrined in a dynamic if slightly hieratic form of realism. Compared with men, women are pretty lightweight, and excluded from the scene of power. Throughout the story, they seem to be reduced to the parts of attendants, sexual for the most part (and mostly provide their “services” to hard-as-nails side-kick Tokai).

Really, how many times does Kyoko, Hojo’s love interest, have to be naked, taking a shower, a bath, or about to be raped (sexual assault is infinitely possible and always imminent in the manga) ? Sigh. That’s where Sanctuary finds its limits, especially when compared with the similar title, Heat, graced by the presence of strong female characters. Having said this, in the context of Japanese politics and yakuza mobsters, women don’t really have a conspicuous role either. From this perspective, the manga can be viewed as somehow faithful to reality. At any rate, as the story rolls along, this never seems to be a major detraction.

This manga is unquestionably a masterpiece, one of the best graphic novels this reviewer has ever read (and reread many times). It ranks easily as one of the most enthralling stories in any category.