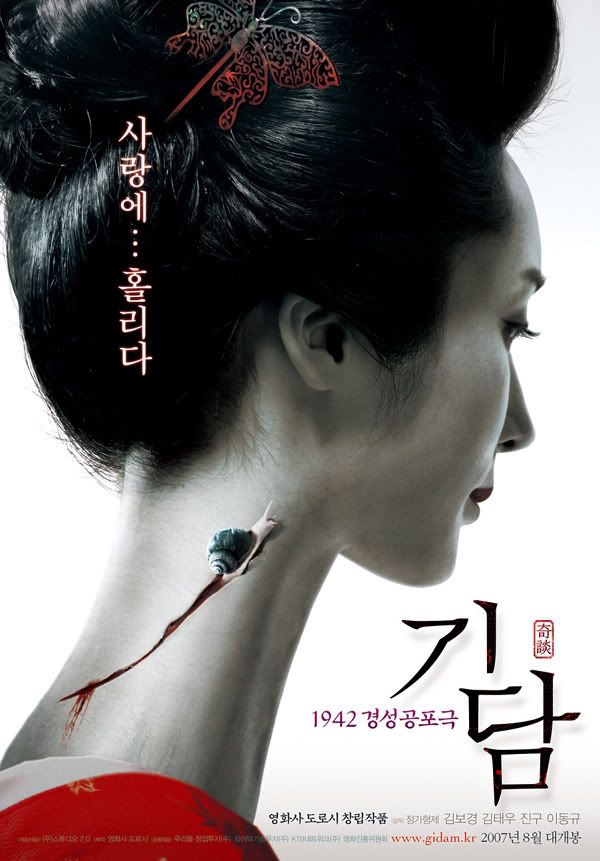

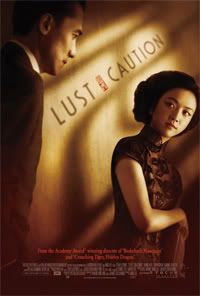

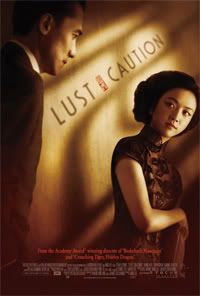

Born in Shanghai in 1920, writer/novelist/screenwriter, Eileen Chang (張愛玲, The Rice Sprout Song, Red Rose and White Rose) died in Los Angeles in 1995. She was nicknamed by a few critics the Chinese Jane Austen (ah, the demon of comparison, but coincidentally, Ang Lee did adapt Sense and Sensibility for the screen). Many of her works described everyday life in Shanghai and Hong Kong under the Japanese rule, while scrutinizing the problematic relations between men and women, her short story Lust, Caution (Si jie) provides the literary inspiration for this brilliant and brutal erotic thriller, the first film that Ang Lee has made in China (since Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon).

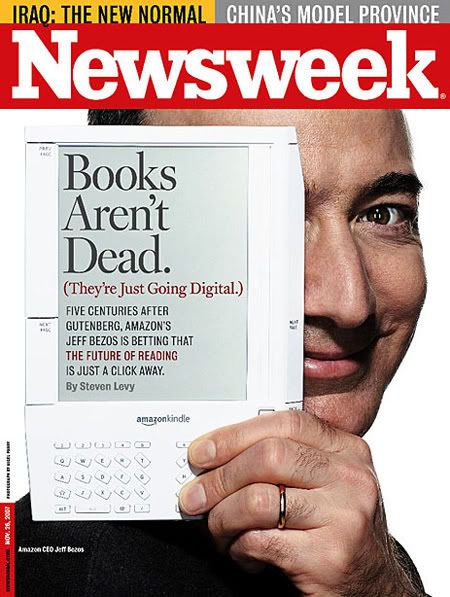

Expectations (including mine) were certainly high for Ang Lee’s new film (which was awarded a Golden Lion in Venice, despite dividing viewers and reviewers) especially after the massive popular and critical success of the gay cowboy drama Brokeback Mountain. With its predecessor, Lust, Caution shares some of the thematic elements, most notably the forbidden love relation. This is where the similarity ends, though. If Ang Lee seems to deal with the same matters here, at least superficially, he does so in a sensibly different manner, and with a more freeform (some would say, loose) cinematic fabric than his previous film.

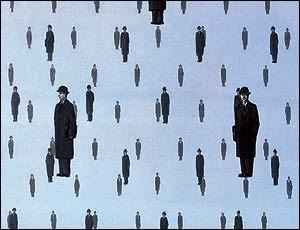

In many ways, the superb opening sequence defines and predetermines the rules and nature of the game that serves as a metaphor for the film as a whole, writing the fate of the main characters in advance, and single-handedly making the film worth a watch: a metaleptic moment during which four chipao-swathed ladies swiftly handle tiles in what appears to be a very intense mahjong game (yet, not a bead of sweat is dropped), while their expressions give out volumes of mute tension, beyond the banter and the bustle of their adroit hands expertly dealing and slapping down the pieces. It soon appears that the youngest of the players, Mak Tai-Tai (Tang Wei) is involved with Yee (Tony Leung), whose wife (Joan Chen) regulaly hosts the social/mental games. On the most banal level, this sequence reveals a beneath-the-surface type of hinter-drama, stoically hidden behind a casual bourgeois décor. More importantly, like all games, the incipit casts the roles of the losers and the winners, a world of shifting identities where something, someone will lose something, him/herself, somehow or other. It is then revelead, in the following scene (a noir-ish French café sequence), that Mrs. Mak, supposedly a rich and bored businesman’s wife, really is Wong Chia-Chi, a young university student turned actress/seductress that might have already long lost her cool, and abandoned her cause in the arms of a villain, as the past flashes back into focus, making it clearer how she came to this.

From then on, Lust, Caution offers a poignant and passionate spectacle that slowly stages the passage à l'acte (in both the sexual and the criminal sense of the expression) by which the loss (of identity, control, caution, etc.), necessarily devastating, will take place and strip the characters from everything, but suffers a bit from the syndrome of over-stretching (the sex starts one hour and a half into the film). A little like in Hou Hsia-Hsien’s Good Men Good Women, (just a little bit) Lust, Caution gives the viewer a glimpse of the lives and times of a small group of students who like the stage and their country (or the idea of it), and get naively infatuated with the idea of killing Mr. Yee (Tony Leung Chiu-Wai), a high-level official and traitor during the Japanese occupation of Shanghai, from 1937 to 1942, at the onset of World War II, before closing up on the dangerous liaison of the spy and the opaque Yee, which is really what Lee seems to be interested in, first and foremost. The narrative proceeds to follow the young (and not so bright) idealists as they decide to take the leap from theatrical representation to political action. Lead by nationalist enthusiast Kuang Yu-Min (a somewhat bland Wang Lee-Hom, famous Chinese pop star), the group amateurishly organizes the murder of the local collaborator, who’s in charge of interrogating (and torturing) his rebellious compatriots. Acting in the name of an ill-defined greater good first, the troupe finds itself back on track a few years later, after the first phase fizzles out and a man gets lamentably and clumsily stabbed by the terrorist wannabees. This time, they come under the stricter supervision of an older resistance leader. Again, in the name of the cause, Chia-Chi accepts to assume the part of the lethal weapon, worldly Tai-Tai: innocence, illusions, and lives will be lost.

To bring down the bodyguard-surrounded Yee, Chia-Chi has to play the role of the sophisticated married woman to win his trust (like a con artist), his heart (like a courtesan) and insinuate herself into his inner ring. One thing leading to another, the young woman winds up surrendering to the game of seduction and letting herself be seduced by her “victim”, and perhaps by the game itself as she succumbs to the passion of playing and being played, which leads her (them?) astray and afar, further and further from her comfort zone, into the dark territories where desire and death lurk at every corner.

Ang Lee’s mastery of the twists and turns of a tortuous narrative is impressive. The most fascinating aspect of the film is the certainly the way he captures auras and intangible atmospheres, the lying eyes and the unspoken truths, as costumes (and masks?) eventually come off and the flesh gives way to an ecstasy that wreaks havoc on the moral certainties of the unlikely couple. The filmmaker relies more on the skin-deep ambiences than dialogues (mostly in Mandarin, with snippets of Shanghaiese) to convey meaning. The result of this is a handful of very compelling sequences, particularly the erotic scenes, in which Lee captures the sense of a relationship based on an intricate mixture of fear and desire.

As in Brokeback Mountain, the main achievement of the film lies in the outstanding performance of the cast, beautifully enhanced by Rodrigo Prieto’s (who is working with Lee for the second time) dark and cold cinematography. Beyond all formal aesthetic considerations, it is truly the the two leads, Tony Leung Chiu Wai and Tang Wei, who breathe life into the film and bestow its true dramatic dimension, and therefore, value on a narrative that wouldn’t transcend the conventions of the wartime spy drama plot otherwise. Leung, who has built a career on showing an incredible range of deadpan-but-hurt-deep-inside faces, from Andrew Lau’s crime thriller masterpiece, Infernal Affairs, to Wong Kar-Wai’s In the Mood for Love and 2046, offers here a first-rate performance as he explores, through the taciturn character, a broad spectrum of emotions. Alternatively surly and sour, always sinister, and sometimes suddenly flaring up, Leung gives an excellent countrapuntal réplique to the spectacular newcomer Tang Wei, who shines through the film.

Despite the heavy historical dimension of the narrative, the filmmakers hardly lingers over the context and skips most of the ideological and espionage small talk (reduced to the ponderous and midly prepostorous “China will not fail” that set off the intrigue), leaving it as a mere backdrop or pre-text, to really get down to the business of characterization. At 136 minutes, the film is mostly structured around the psychological joust that sketches out between the lovers, who discover and uncover each other in a spinning arena of mixed emotions and contradictory feelings. It takes some time for the pieces of the puzzle to come together and the impatient viewer might find this very lengthy and laborious in the end.

Despite what some viewers and critics have seen as problem of pace, Lust, Caution is still a fascinating piece that makes a consummate shows of the fatal strategies that are set up along the way, in parallel to the march of history. Progressively and painstakingly, the process of sexual seduction develops into the locus and sole engine of pure emotion. In fact, James Schamus and Hui-Ling Wang’s scenario takes meticulous and perhaps excessive care not to rush anything, building up the emotions into a surprising apex: the quasi-rape of the ingénue, who nevertheless gives in to the ruthless and sadistic thrusts of Mr. Yee, with careless abandon in the heat/paroxysm of the moment.

The thriller aspect of the narrative, once the characters lose themselves to each other, become ancillary and should probably have effaced itself from the screen to leave more space for these thrills (even though they come aplenty). Indeed, the film truly finds its raison d’être in the sexual duality of the two protagonists, one that admits no third parties (or loyalties for that matter)

In Brokeback Mountain, the love story took center stage and the sex was almost peripheral. Here, things work the other way around. Sex, raw, real (visibly unsimulated), and shot in the most carnal manner possible, accounts for the psychological undoing of the characters. It constructs the labyrinthic tale of a steamy/stormy liaison in/by which the couple fucks each other (and themselves) to their doom.

Nothing short of fascinating in this respect, Lee’s Lust, Caution is a film that adeptly blends the sexual and the sublime, favoring the personal at the expense of the historical. Strangely, the conclusion seems to say, feelings are not enough to sustain the blend... and Mr. Yee’s eyes let a few helpless tears bleed and concur. Love’s labour’s lost, said somebody.

Technical info:

Production Company:

Mr. Yee Productions LLCExecutive Producer: Song Dai, Ren Zhong Lun, Darren Shaw

Producer: Bill Kong, Ang Lee, James Schamus

Screenplay: Wang Hui Ling, James Schamus, based on a short story by Eileen Chang

Cinematographer: Rodrigo Prieto

Editor: Tim Squyres

Production Designer: Pan Lai

Sound: Philip Stockton, Eugene Gearty

Music: Alexandre Desplat

Principal Cast: Tony Leung Chiu Wai, Tang Wei, Joan Chen, Wang Leehom