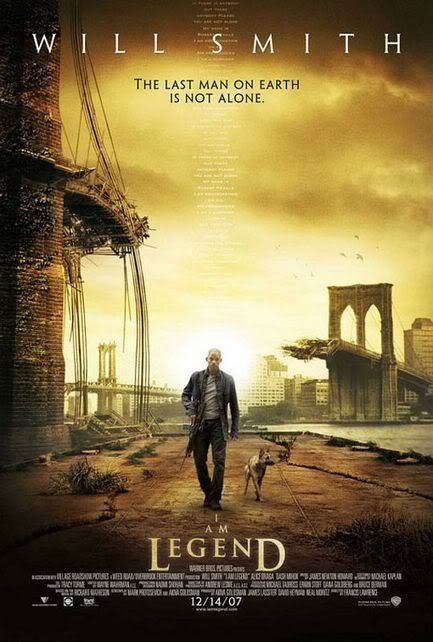

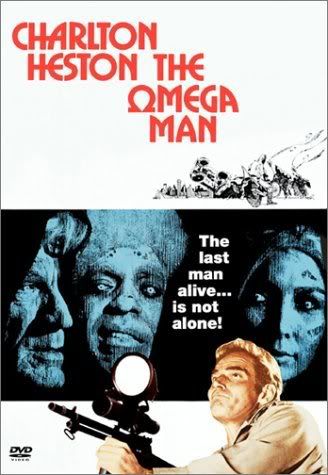

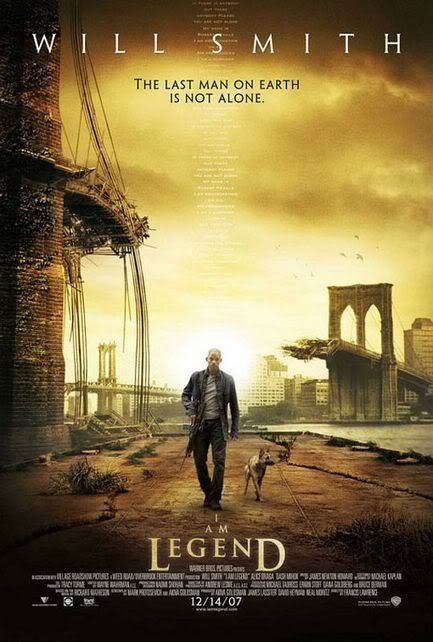

The project of a supersize adaptation of Richard Matheson’s sci-fi novel (1954) has been one of Hollywood’s hot potato games for the past ten years. Ridley Scott, among others, juggled and struggled with a version tailor made for Schwarzenegger’s 12 pack. Bringing the film to life was no mean feat, especially considering the seminal quality of the book it is based on, in the field of modern horror fiction. Matheson widely considered to be the spiritual father of Romero’s zombies (the filmmaker himself confessed deriving his inspiration from the novelist). Two adaptations were made, at a time when the threat of nuclear warfare haunted (creative and collective) imaginations: The Last Man On Earth, an odd American-Italian co-production by Sydney Salkow and Ubaldo Ragona (1964) with Vincent Price, and The Omega Man by Boris Sagal (1972), a half-forgotten flawed (and a tad outdated at that) gem that pitted Charlton Heston against a sect-ish group of hooded zombies, emphasized the sacrificial dimension of a man who managed to redeem what little remained of humankind: the hero became a new messiah.

Francis Lawrence, who signed a few music videos for Justin Timberlake and was the man behind the helm of Constantine (an aesthetic success, if not exactly a great movie), inherited the duty of directing the post-apocalyptic “Robinson Crusoe castaway” tale by Matheson.

The film is a blast on several grounds, but mostly stands out of the recent surge of sprinter-zombie flick fare by the straightforward but modest manner in which it puts the tight and slightly depressive storyline of the book on new tracks, far from standard action-movie pacing and storytelling. It manages to maintain for quite a while (considering it is after mainstream Hollywood stuff) a first-degree, fervent manner of wandering around the possibilities that the narrative opens up, lingering over the dry beauty, with patience and without forcing the , and developing an almost ideal (yes, too bad) dosage of effects.

The plot might seem paper-thin, and can hold in a couple of sentences, but works fine:

A mutated virus designed to cure cancer has gone wrong and decimated the human species. The 10% left alive have been infected with a form of ultra-hardcore rage and transformed into feral, nocturnal creatures that are not unlike vampires, and could actually pass off easily as clones of Klaus Kinski’s Nosferatu. A few (1% of humanity), were miraculously immune against the man-made disease but fell prey to the bald, cannibalistic, infected group. One man, Robert Neville, a military scientist, still entertains the fantasy of finding the cure and “fixing it”. In the ruins of a megapolis (originally L.A., here: New York of course, I’ll come back to it), apparently the last survivor of the worldwide biochemical disaster, roams the deserted streets and avenues during the daytime, while the horde of mutants lurk in the lower, darker depths of the Big Apple, away from the sunlight. As night falls, the uglies come out and spread all over the city, forcing Neville to hide in his comfy barricaded Washington Square pad until the flesh-eating loonies get tired of howling at the moon.

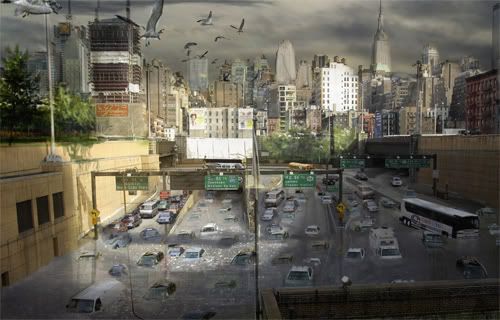

What Lawrence’s film does best is setting a context, as the melancholy camera hovers over the desolation in long, amorphous tracking shots of New York, freeze-framed by the catastrophe. The return of nature and wild life through the cracks of the concrete bestows an almost pastoral, meditative character to the hour-long mise en place of the survivor’s day-to-day existence. The foremost achievement of I Am Legend may be in the lengths to which it expands/extends the post-doomsday chronicle of the lonely times of Robert Neville as a middle-aged idler, one of the main charms of the book. Unhurriedly, the film takes pains to construct a life of loafing around the narrow edge of reason and crack-up, but ordered like clockwork around a set of fixed habits, against the bleak broken down backdrop of the devastated cityscape: Neville pumps gas at an abandoned (of course) station, loots a Tribeca apartment for canned fish, runs some more errands, goes deer-hunting and back home, where he chain-watches dvds and recordings of the Today Show, the futile reminders/remains of an obliterated civilization. Will Smith turns out to be quite the ideal last man on earth, against all odds. Brainy (he’s a virologist after all), brawny (he works out), and musical (he listens to Bob Marley on his iPod), he provides a rock-solid emotional anchor for the viewer and could have carried the whole film on his shoulders, had he been given the chance.

One the most beautiful ideas of the film relies on a minimum of effects : to retain a sense of humanity and social connection, Will Smith talks to mannequins that he has arranged in a mockery of a typical urban life routine, as stand-in shoppers and clerks in a dvd store, where he borrows items every morning. Never had the actor appeared so isolated, devastated, worried, obsessive, desperate, etc. while pulling off the part of the nicest (and only) guy around.

This logic of restraint, patiently established in this magnificent, much talked-about opening, craftily paves the way for the moments of pure, delirious frenzy that drill holes in the vegetative framework: the few overheated (and somewhat underestimated) sequences of confrontation with the enraged ghouls, are impressive displays of digital, hyperkinetic brutality, in the wake of the revisionist trend that Snyder’s Dawn of the Dead and Boyle’s 28 Days Later initiated.

In the midst of this CGI fest, Lawrence has nevertheless shot an outstanding but sober in-the-dark scene reminiscent of the videogame Silent Hill (the most formally successful action sequence of the film).

The mushy sentimentality of the flashbacks that punctuate the narrative pales in comparison and constitute the most problematic part of the film: we catch brief glimpses of the chaotic evacuation of New York and terrified exodus that takes place, following the quarantine of the city. But these are less occasions of showing the magnitude of the disaster than familiarizing it (and neutralizing it) as a family drama by showing the protagonist with his wife and kids, in typical Hollywood fashion and establishing the emotional link with the nice little doggy, Samantha (always nice to have a good German shepherd around when you’re the last man on earth).

The film unfolds according to a logic of restraint, fully circumvallated by fear, and the very treatment of the massive zombie attacks, in the mode of pure sideration, underscores the contemporaneity of the tale with today's age of terror/terrorism. The post-9/11 dimension the film is constantly referred to (the devastated site of New York is baptized “ground zero” by Neville himself), not to mention the post-traumatic, guilt-ridden psychological profile of the character, which speaks volume about the clean break it makes with the 1970’s formula - the hero as savior, and so on and so forth. Some might object to the ample rewriting of Matheson’s original material, most notably the conclusion, but on the larger scale of the history of the genre, I Am Legend writes itself as a landmark that should not be neglected.